I've just booked a place at Children and Young People Now's 'Keeping Children Safe Online' conference. It's not a conference title I'm entirely comfortable with. It appears to embody two key errors in thinking about young people and the internet

-

An over-emphasis on risk

-

The wrong response to risk

In exploring my concerns on these points, the provisional thoughts and explorations I've been working through emerged as this blog post.

An over-emphasis on risk

It's easy to talk about risks. When you're looking for the possibility of trouble – you can usually find it. And when you've identified trouble – the (cognitively) 'easy' response is to put up fences – block it off and 'protect' people from it. If you can stop one person from experiecing the 'risk' – then putting up the fences is worth it. The logic follows that risks are bad – and risks should be removed.

Lizzie Jackson perceptively writes:

“What concerns me is the child protection industry which is increasing apace and, through its expansion, it could be argued, the promotion of the perceived risks to children.”

It's far trickier to talk about:

a) Navigating risk – that altogether more sutle process of possessing the right skills, having the relevant cognitive and emotional assets, accessing the right advice, and being in the right settings to turn what could be a seen as a potential 'trouble' situation into an opportunity for individual development.

b) Opportunities – If 'all risks are bad' are all opportunities good?

Opportunities are prospective, provisional spaces for exploration. We don't know exactly where they lead. We can't specify what will definitely happen when an opportunity is pursued. And most opportunities involve some risk (which, by implication, makes them bad?). If you tell me not to do something because of the risk, you know what happens. I don't do it. If you encourage me to explore the opportunity, sensitive to navigating risk, then you need to accept you don't know exactly what is going to happen. That can be tricky.

The wrong response to risk

The recent BBC Panorama documentary 'One Click from Danger' suggested that, in response to risks online, under 18's should not use their real names and only talk to those they have had real world contact with.

That's a set of recomendations that cut young people off from a rich range of opportunities and experiences for social interaction and development online.

And it's a set of recomendations that entirely ignore the crucial role of young people's participation in their own protection.

*

*

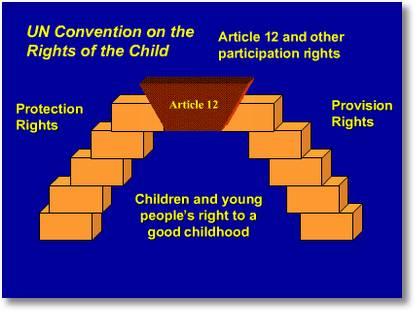

The slide above (a rightful favorite of Bill Badham's) outlines how young people's right to participate is the keystone that holds together their rights to be protected, and their rights to provision. Effective protection can only happen through participation.

We should be engaging young people in all the decisions that affect their online lives – not setting down arbitary rules that exclude them from key decisions and fail to engage young people in managing risks in partnership with trusted peers and adults around them.

Asking the right questions

How can adults keep young people safe online? They can't. Not on their own. And certainly not by using inflexible rule and systems of control.

Rather – we need to be asking about how we can support young people to be safe online? And – how we can support young people to make the most of the opportunities and provisions available online?

Or to rephrase the question into a form that might provide a little for structure for discussion and sharing of practice:

What does young people's effective participation in their own protection, and the provision for them, look like in the online context?

*As an (important) aside – given the UK has signed the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child from which the rights in the model above come – surely it should form the basis for our public policy in this area?

This may seem to simplistic – but there must be parallels between how we deal with roads and how we should deal with the web.

We teach our children to cross the road safely, yet currently our schools’ approach to the web is akin to preventing a child ever going near a road.

whole heartedly agree – I think a big factor is the lack of familiarity with the technologies by adults. Until adults understand these things themselves I think theres a ‘fear of the unknown’.

On the otherhand thats not to overlook that from my own experience there are a lot of young people that are not assessing risks when online. I like the ‘Internet Highway Code’ idea!

Nick, Mike

There is indeed a parallel. With road safety we educate young people, and give guidance to help them navigate risks – and in particular, be aware of their limitations in terms of judging speed/distance etc.

An ‘Internet Highway Code’ is an interesting idea – although that highlights two spaces where the crucial role of young people’s participation in their own protection comes in. Firstly, any code would have to be drafted very much between young people and adults.

The possibility of a code emerging that was unrealistic and did not match the reality of young people’s lives is high if the code contents is not very carefully negotiated between young people and adults (and a diversity of adults who champion both opportunity and safety). (I.e. young people must participate in the setting up of the structures for their protection).

A code cannot be taken as a set of rules to apply from age 0 – 19. And it cannot operate alone. Here is where the online realm is different from the road – and from a highway code. A highway code sets up clear expectations between drivers and pedestrians. There is no need for the code to be different for a 5 year old from a 15 year old. However, a parent may encourage a 5 year old to always hold their hand near the road, or may negotiate other developmental-stage-appropriate restrictions with the young person. Online, a) there may be a case for different guidance for different ages, and b) that process of negotiation to play an even larger role.

Out of time to reflect more on this right now. But I think when I’m talking ‘participation in protection’ that there is a literature on young people’s involvement in care proceedings that has explored this a lot – and I’ll see what I can do to track that literature down. (All pointers welcome…)

True – and perhaps you should still be ‘holding the hand’ of a 5 year old using the internet?

The BBC suggestion that children/young people only speak to people they know in ‘real life’ is futile and also wasteful – imagine telling your children only to speak to people they know at school or at playgroups/youth clubs!! I think these kinds of ‘limiting’ rules are less effective than positive guidance on how to do/use things.

Any ‘code’ would have to be drawn up by people with knowledge and interest – that includes parents, teachers & practitioners, web developers & managers and of course children & young people.

I think social networking sites should probably be held to be more accountable too – if you create a network and are then not able to manage it effectively because you didn’t plan for how many people will use it and therefore can’t effectively manage it arguably you are negligent. If you set up a childrens play group you would be expected to provide an adult:child ratio appropriate to the age level of the children you work with – perhaps something similar should apply to online networks that allow children/young people to register?

It’s simple – educate, don’t leglislate: http://www.mediasnackers.com/report/2007/December/05/525/

🙂

Apart from it’s not so simple.

It’s not politically simple:

Barriers and legislation make us feel safe. It empowers the state. The state can feel it is doing its duty.

Education empowers the individual – and the state’s fulfilment of it’s (assumed?) responsibility to keep young people safe is conditional on the behaviour of young citizens who it cannot directly control.

(You can probably replace state with ‘parent’ in the above argument and find it still broadly works if you want to take that level of analysis…)

It’s not philosophically simple

Imagine two countries each with 100 young people in. Both start with an equal range of risks and opportunities for young people accessing the internet.

The first uses legislation and restriction to control young peoples internet access. Opportunities are massively curtailed for everyone, but – no-one comes to significant harm.

In the second, education is used to equip young people to navigate risk online. The full realm of opportunities are open to them, but, 2 young people come to harm.

Can we trade really accept the increase in harm in order to gain the increase in opportunity of the second option?

(This thought experiment could do with a lot more development – and is a bit of a straw man to come back to later. I’m sure others out there have worked on similar thought experiments – all pointers welcome…)

It’s not practically simple

The skills and literacies to make the most of the online world, whilst managing negative aspects of the web, are complex and nuanced ones.

The investment to develop the depth of skills needed for effective engagement with the web is significant.

Why complicate things?

It’s far too each for the debate about young people’s rights and safety to end up wholly driven by emotion.

But in this case – I’m not sure emotion is going to get us the right answers. (Emotional responses are pat of it of course – but they’re only one part). We need some real discussion and deep thinking about this one…